Research into the evolution of the

Lewisian Complex (LC) has taken place against a wider backdrop of global geological investigations into the evolution of

Archean and

Proterozoic continental crust. It is reasonable to suggest there is some controversy over the proposed models and geological processes forming the early continental crust i.e

Archean subduction. The evolution of the LC spans the Archean/Proterozoic boundary where profound changes in the earths geological processes have happened and where some proponents of plate tectonic theory believe embryonic plate tectonic processes started. The LC is an outdoor laboratory for geologists to test new techniques and concepts of geological processes operating in the Archean and Proterozoic.

|

| Glaciated mafic gneiss ~ Lewisian Gneiss Complex, NW Highlands of Scotland |

The mainland Lewisian Complex (LC)

outcrops have been visited and investigated by geologists from all over the world seeking answers to some fundamental questions on the formation and evolution of the continental crust. The reason the LC has been studied for over a century is the complexity of the geology. The illustration below is a detailed geology map of a few square metres exposure of the LC

(Pink = Amphibolite facies TTG gneiss, Green = metadolerite dyke, Brown = Pegmatitic granite). The geological history of the outcrop with the oldest event first :

- Melting of hydrated mafic rocks (Amphibolites?) and magmatic emplacement of the felsic gneiss protoliths: Tonalite-Trondhjemite-Granodiorite aka TTG.

- Badcallian deformation and prograde metamorphism of the TTG gneiss (Granulite facies metamorphism).

- Possible Inverian deformation and retrograde metamorphism of Badcallian gneiss to Amphibolite facies with an influx of water.

- Dolerite dyke intrusion (member of the Scourie Dyke swarm).

- Laxfordian deformation and retrograde metamorphism of the dyke and any remaining anhydrous Badcallian gneiss minerals to Amphibolite facies with an influx of water.

- Intrusion of pegmatitic granite.

- Late-Laxfordian folding.

|

| Illustration of Lewisian Gneiss complexity and sample locations from John M. MacDonald, Kathryn M. Goodenough, John Wheeler, Quentin Crowley, Simon L. Harley, Elisabetta Mariani, Daniel Tatham, Temperature–time evolution of the Assynt Terrane of the Lewisian Gneiss Complex of Northwest Scotland from zircon U-Pb dating and Ti thermometry, Precambrian Research, Volume 260, May 2015, Pages 55-75, |

The previous

post covered some simplistic 2 dimensional illustrations of rock deformation, gneiss formation and a brief overview of the Lewisian Complex in the 1907 memoir 'The Geological Structure of the North West Highlands of Scotland'. Based on field work and petrological analysis the memoir proposed that the LC was made up of gneisses with affinities to igneous rocks with a minor proportion of presumed sedimentary rocks and a great series of intrusive rocks. The mainland LC was broken down into three districts on the generalised style of deformation and mineral assemblages.

|

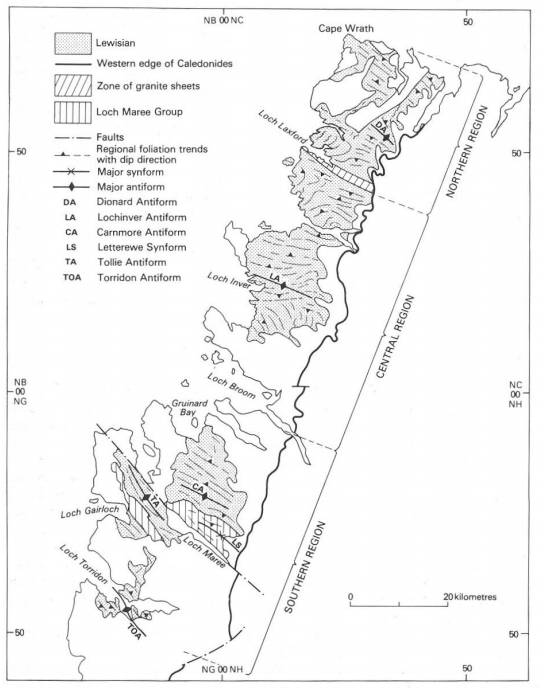

| Lewisian Gneiss Complex mainland outcrop map from Johnstone, G.S., Mykura, W., 1989. The Northern Highlands of Scotland. |

The 1907 memoir dedicated three chapters naming and describing the petrology of the rocks comprising the Lewisian Complex. Since then geologists across the world have used an increasing number of names to identify and describe metamorphic and igneous rocks, there has been confusion especially when comparing past with current papers or from papers by international authors. In an attempt to clarify past terms and establish some consistency In 2007 the British Geology Survey issued web versions of Recommendations by the IUGS subcommission on the systematics of metamorphic rocks. They also make a useful reference point in penetrating the jargon of metamorphic geology and provide historical overviews of terms.

- How to name a Metamorphic Rock

- Types, Grade and facies of Metamorphism

- Structural terms including fault rock terms

- High P/T metamorphic rocks

- Very low to low-grade meatamorphic rocks

- Migmatites and related rocks

- Metacarbonate and related rocks

- Amphibolite and Granulite

- Metasomism and metasomatic rocks

|

| Detail of supracrustal rock, metamorphosed to granulite facies grade. |

As the controversies surrounding the rocks of the LC encompass a broad spectrum, this blog post will confine itself to just some of the key events and geological controversies that have developed as investigation into the mainland LC has progressed. Published research on the mainland LGC was relatively quiet for the next 4 decades from the memoir publication in 1907 until 1950 when a landmark paper was published:

The pre-Torridonian metamorphic history of the Loch Torridon and Scourie areas in the North-West Highlands, and its bearing on the chronological classification of the Lewisian.

Summary

The paper describes the metamorphic history of two areas of Lewisian gneiss in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. Metamorphosed sedimentary rocks are described for the first time from the Loch Torridon area. It is shown that both in the Loch Torridon and the Scourie districts the gneisses have been produced in two separate periods of metamorphism, migmatization and deformation. These two metamorphic episodes, which are named the Scourian and Laxfordian episodes, are separated in time by a period of uplift and tension during which a series of uniform dolerite dykes was intruded. Since a very great interval of time appears to have elapsed between the two metamorphic episodes, it is suggested that the rocks produced during these episodes should be regarded as members, not of a single formation as heretofore, but of two distinct chronological units.

John Sutton, Ph.D., F.G.S. and Janet Watson, Ph.D., F.G.S. February 1950 Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 106, 241-307.

The paper provoked an

exchange of letters in the Geological Magazine 1951, that highlight the nature of controversies. Nonetheless, whilst the assignment of metamorphic chronology was generally considered ground breaking, the belief in

granitisation of sedimentary rocks as the origin for the gneisses caused controversy throughout the 1950's and '60's, until finally in the 1970's there was unanimous agreement with the 1907 memoir that the gneisses had originated from igneous rocks. The implications of a magmatic origin instead of sedimentary origin for the gneisses required a new model for the development of the LC. The assertion that the Scourie Dykes were a series of uniform dolerite dykes intruded in one event, was also challenged from field evidence and mineralogy.

|

| Screengrab of the BGS map of the Scourie Dyke Swarm and Sron a' Bhuic |

The 1907 memoir clearly illustrated the cross cutting relationships of epidiorite (quartz dolerite) and picrite (ultramafic) dykes (Fig 7 p163) south of Loch Assynt at Sron a' Bhuic, where deformation was low in other areas cross cutting relationships were noted between dykes. In the Gruinard district dykes demonstrate 3 episodes of cross cutting relationships, although all have been retrogressed to Amphibolite facies mineral assemblages. There is also other field evidence that demonstrates a period of time separating the members of the Scourie dykes :

- Some Scourie dykes have distinctly chilled margins and appear to be structural controlled by joints in the surrounding gneisses implying intrusion into gneiss that was once brittle and 'cooler' rock, whilst other dykes unaffected by later metamorphic and deformation events have margins indicative of intrusion into hotter rocks. The disparity may be due to separate events of intrusion or slices of deeper/shallower crust might have been juxtaposed together in later Laxfordian deformation events.

- Unretrogressed 'fresh' dykes cut across retrogressed dykes.

- Undeformed dykes that cut across deformation that appear to be Laxfordian.

- To complicate matters still further: detailed fieldwork and petrological examination suggests that some dykes were autometamorphosed on emplacement into hot rocks with abundant water present. Petrology of the Scourie dyke, Sutherland. O'hara, M.J., 1961. Mineralogical Magazine, 32(254), pp.848-865.

There is still ongoing controversy over the mainland Scourie Dyke ages, sequence of intrusions etc.

|

Scourie Dyke core drilled for samples.

|

1961 saw a research paper published

A Geochronological Study of the Metamorphic Complexes of the Scottish Highlands Giletti, B. J., Moorbath, S. and Lambert, R. S. J.

February 1961 Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 117, 233-264. That dated Pegmatites associated with the Scourian part of the Lewisian complex at least 2460 m.y. old, whereas the Laxfordian metamorphism occured about 1600 m.y. ago. The dates provided evidence that there was indeed a vast amount of time between the Laxfordian metamorphism and the gneiss formation deep in the Scourian.

|

| Pegmatite vein cutting highly strained Mafic Gneiss |

Whilst the 1907 geology maps were detailed at 6" to the mile, they were compromised by the quality of topographic maps then available, consequently in the 1960s, 70's and 80's geologists rectified this with detailed mapping activities. In the 1960's detailed mapping and petrological examination in the Lochinver area determined deformation of earlier Scourian gneiss banding and structures and/or static retrogression of the Scourian granulite facies metamorphic gneisses. This deformation and metamorphic retrogression was then intruded by Scourie dykes, which ruled out a Laxfordian age of metamorphism The new event was named the Inverian. However, both the Inverian and Laxfordian metamorphic events were similar in deformation style and metamorphic grade, so in lieu of chronological dates, the Inverian deformation/metamorphic retrogression could only be unambiguously differentiated in the field by ascertaining whether the Scourie Dykes cross cutting the gneiss were also unaffected by Laxfordian metamorphism.

Every so often a geologist has to publish a paper in an attempt to establish some clarity, using chronological dates and field observation

Observations on Lewisian Chronology

Synopsis

Evidence relating to the chronology of the Lewisian is reviewed in five categories in the light of recent differing interpretations.

- Metamorphic and migmatitic episodes—the restriction of the term Scourian to a time period is urged. ‘Badcallian’ is proposed for the early Scourian (c. 2600 m.y.) episode, Inverian being well established as the late Scourian (c. 2200 m.y.) episode. The sub-division of the Laxfordian (? 1800–1400 m.y.) is discussed—the younger dates (c. 1100 m.y.) may refer to a younger orogeny.

- Scourie dyke suite—although four tectonically separable suites have been proposed, the evidence is consistent with a single suite.

- Structural episodes and sequences—unjustified correlation has led to over-elaborate structural chronology.

- Gairloch–Loch Maree sediments—evidence points to a post-Badcallian pre-Inverian age but the existence of large areas of gneisses of this age is doubted.

- Other basic and ultrabasic intrusions—chronological implications are discussed.

Finally it is argued that since the major tectonic re-orientation of the Lewisian seems to have occurred in the Inverian, there is a case for placing an orogenic break within the Scourian.

R G Park.December 1970 Scottish Journal of Geology, 6, 379-399.

Which prompted a

letter of reply highlighting some issues.

In 1974 a research paper describes in some detail the effects of Inverian metamorphism:

The Lewisian of Lochinver, Sutherland: the type area for the Inverian metamorphism Evans, C.R., Lambert, R.S., 1974. Journal of the Geological Society, 130: 125-150.

Nature, 204: 638-641. The paper is also one of the few sources to quantify the water influx to retrogress the anhydrous minerals of the granulite facies gneisses to hydrated minerals of Amphibolite facies. Mapping of metamorphic minerals suggested that shear zones had acted as conduits for the water. In a 1982 paper

The retrogression of ultramafic granulites from the Scourian of NW Scotland. Sills, JANE D., Mineralogical Magazine 46, no. 338 (1982): 55-61. The water required to retrogress the granulite facies rocks was quantified as 1 cubic kilometre of water to retrogress 50 square kilometres, 1 kilometre thick. To date the origin of the water influx remains uncertain.

The 1970's and 80's witnessed investigations on structural models, metamorphism and geochemistry, with geochemical analysis mostly concentrated on the granulite facies rocks (ultramafic, mafic, TTG and

supracrustal) and the Scourie Dyke suite. Attempts were also made to correlate the the LC with other worldwide Archean/Proterozoic formations.

A 3rd Lewisian conference was held at Leicester University in 1985, to facilitate an exchange of ideas and to produce an up to date publication on the LGC. In 1987 the

Geology Society Special Publication No 27 'Evolution of the Lewisian and Comparable Precambrian High Grade Terrains was published. Papers of note for their relevance to structure and history of the LGC.

The Lewisian complex: questions for the future. John Sutton and Janet Watson p7-11. A series of problems presented by the LGC where further research should be concentrated.

The Lewisian complex. R. G. Park and J. Tarney p13-25 A contemporary overview of the Archean and Proterozoic evolution of the complex and comparison made with other high grade terrains around the world.

The magmatic evolution of the Scourian complex at Gruinard Bay. H. R. Rollinson and M. B. Fowler p57-71 From detailed field mapping and geochemical analysis they summarised the magmatic/metamorphic history of the Scourian rocks in the Gruinard area as follows :

- Amphibolites (basaltic lavas ?)+layered complexes. Tonalitic magmas emplaced.

- Deformation and (?) metamorphism.

- Trondhjemite and granite magmas emplaced.

- Deformation and amphibolite to hornblende granulite-facies metamorphism.

- Retrogression.

On the basis of experimental work it was postulated that amphibolites were the likely source rocks for the quartzo-feldspathic (TTG) rocks in the Gruinard area.

The role of mid-crustal shear zones in the Early Proterozoic evolution of the Lewisian. M. P. Coward and R. G. Park p127-138 Synthesis of previous and current structural research on metamorphic fabrics, geophysical seismic survey data et al to produce a structural and kinematic model for the whole of the Lewisian.

The late '80's and '90's witnessed chronology work to pin down specific events and in 1996 a paper highlighted some issues with the dating methods :

Conflicting mineral and whole-rock isochron ages from the Late-Archaean Lewisian Complex of northwestern Scotland: implications for geochronology in polymetamorphic high-grade terrains.

Whitehouse MJ, Fowler MB, Friend CR. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1996 Aug 1;60(16):3085-102.

From the conclusion

'At Gruinard Bay, detailed consideration of field, petrographic, and geochemical data has enabled us to select probable cogenetic groups for inclusion on whole-rock isochrons which, in principle, should be less susceptible to the effects of pervasive retrogression. This approach yields information which leads to a consistent, unambiguous sequence of events in complete accord with that established in other parts of the Lewisian Complex.

Until the '90's the mainland LC had been thought to be a single coherent block of continental crust, however chronological dating with radiometric isotopes produced a range of dates across the LC and associated controversy. One model that could accommodate the range of dates, differing rock geochemistry and metamorphic grades, across the regions was

terrane assembly.

In 2001 a paper was published

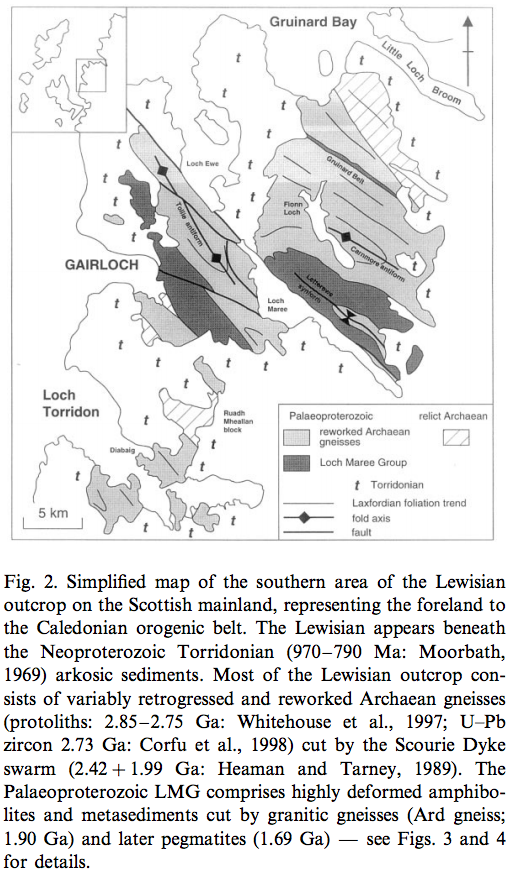

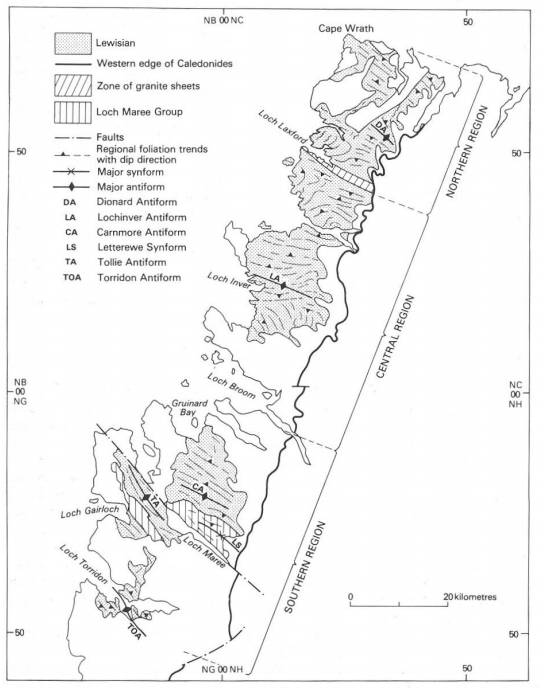

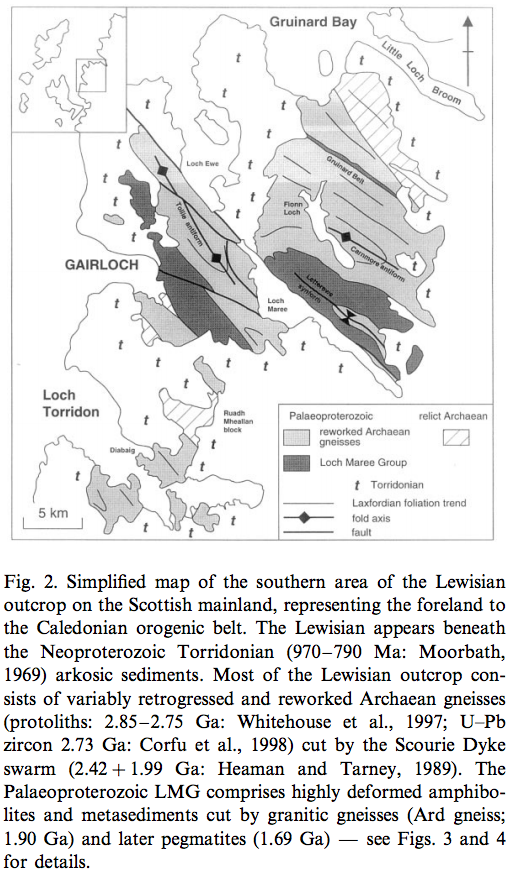

covering The Loch Maree Group: Palaeoproterozoic subduction–accretion complex in the Lewisian of NW Scotland, R.Graham Park, John Tarney, James N. Connelly, Precambrian Research, Volume 105, Issues 2–4, 31 January 2001, Pages 205-226,

|

| Illustration from Park, R. Graham, John Tarney, and James N. Connelly. "The Loch Maree Group: Palaeoproterozoic subduction–accretion complex in the Lewisian of NW Scotland." Precambrian Research 105.2 (2001): 205-226. |

|

| Illustration from Park, R. Graham, John Tarney, and James N. Connelly. "The Loch Maree Group: Palaeoproterozoic subduction–accretion complex in the Lewisian of NW Scotland." Precambrian Research 105.2 (2001): 205-226. |

|

| Highly strained Amphibolite (metabasalt) of the Loch Maree Group. |

2002 R. G. Park published a Memoir on the Lewsian Geology of the Garloch district.

In 2001 P. D. Kinny C. R. L. Friend published

A reappraisal of the Lewisian Gneiss Complex: geochronological evidence for its tectonic assembly from disparate terranes in the Proterozoic.

In 2004 G. J. Love, P. D. Kinny C. R. L. Friend published a paper "

Timing of magmatism and metamorphism in the Gruinard Bay area of the Lewisian Gneiss Complex: comparisons with the Assynt Terrane and implications for terrane accretion". This paper proved particularly contentious and F. Corfu (2007) issued a reply to the paper:

"The paper also presents new insights on the systematics of zircon in high-grade rocks, however, it also contains some dubious interpretations that ignore or misrepresents available evidence."

In 2005 the authors published a paper revising the mainland and offshore LGC into terranes.

Proposal for a terrane-based nomenclature for the Lewisian Gneiss Complex ofNW Scotland Kinny, P.D., Friend, C.R.L., Love, G.J., 2005. Journal of the Geological Society,

162: 175-186.

An acknowledgement hinted at the controversy amongst those who had discussed the paper before it was published :

"R. G. Park is thanked for many long discussions dealing with problems of general Lewisian Gneiss Complex evolution and its nomenclature. The many detailed comments of D. R. Bowes, who fundamentally disagrees with most of what is presented here, were extremely helpful in assisting us to clarify some of our ideas. Additionally, M. B. Fowler, K. Goodenough and R. A. Strachan made many helpful comments on early drafts. The reviewers, S. Daly, J. Mendum and R. G. Park, are thanked for their constructive and detailed comments."

|

| Kinny, P.D., Friend, C.R.L., Love, G.J., 2005. Proposal for a terrane-based nomenclature for

the Lewisian Gneiss Complex of NW Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society,

162: 175-186. |

The paper generated some controversy from other geologists questioning dates, omissions, interpretation of field relationships, tectonic modelling, the number of terranes and timing of events.

In 2005 R.G. Park published

The Lewisian terrane model: A review. Scottish Journal of Geology 41(2):105-118 · November 2005. Proposing that instead of the multiple terranes there were simpler models compatible with field evidence to explain the evolution of the continental crust with varied ages and geochemistry i.e the juxtaposition of differing levels of crust, intrusion of different plutonic rocks emplaced at different dates, intraplate movements etc.

In 2007 R.G. Park was quoted "Interpretation of geochronological data. This has been particularly controversial! How do we interpret whole-rock ages? Are we dating protolith or metamorphic ages? Are we dealing with a single piece of Archaean crust with a complex history of crustal accretion or with an amalgamation of terranes of differing provenance?"

The ambiguity of chronological dating was demonstrated in a paper published in a 2010 Geological Society Special Publication 335, Continental Tectonics and Mountain Building The Legacy of Peach and Horne :

On the difficulty of assigning crustal residence, magmatic protolith and metamorphic ages to Lewisian granulites: constraints from combined in situ U–Pb and Lu–Hf isotopes p. 81-101. The Special Publication was comprised of papers derived from a joint Geological Society of London/Geological Society of America conference in 2007 celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the publication of the 1907 memoir on The Geological Structure of the North West Highlands of Scotland.

The publication included two other papers on the LGC :

The Lewisian Complex: insights into deep crustal evolution. J. Wheeler, R.G Park, H.R Rollinson, A Beach 51-79 An historical and contemporary overview of geological investigations and a review of the geochemical work, metamorphism, chronology etc. Noting that chronological dating had produced some ambiguous results, the behaviour of minerals used in dating metamorphic events was complicated and the issues with a multiple terrane assembly model. The questions asked by John Sutton and Janet Watson, at the 3rd Lewisian conference in 1987 were still waiting for answers two decades on and that there was "scope for geochemical and tectonic views of the Lewisian to become more integrated".

|

| Granitic Pegmatite vein cutting mafic gneiss (Scourie dyke) in the Rhiconnich terrane/Northern region of the mainland Lewisian Gneiss Complex. |

The special publication also featured a third paper that coincidentally integrated geochemistry and tectonic views:

The Laxford shear zone: an end-Archaean terrane boundary? Goodenough, K. M., R. G. Park, M. Krabbendam, J. S. Myers, J. Wheeler, S. C. Loughlin, Q. G. Crowley, C . R. L Friend, A. Beach, P.D Kinny, R H Graham. p103-120. The paper presented a comprehensive overview of previous geological research associated with the Laxford Shear Zone, Assynt terrane (northern part of the Central region) and Rhiconnich terrane (Northern region). A constraining event for possible terrane amalgamation was provided by new geochemical analyses of Scourie Dykes in the Rhiconnich Terrane correlating with Scourie Dykes in the Assynt Terrane. The criteria for terranes was assessed against field relationships, geochemistry and dates which indicated the Laxford shear zone may well qualify as a terrane boundary formed circa just after the Archean/Proterozoic boundary and during the Inverian event. However, the possibility still remained that the Laxford Shear zone separated two different areas of a continent that were juxtaposed together by intra-plate movements during the Inverian event. The paper also highlighted a number of areas for future research to explore.

|

| Exposure of metamorphic mafic gneiss and presumed 'brown' gneiss, that possibly represent supra-crustal rocks before being metamorphosed. |

2010 is a reasonable point to draw a line under the nature of controversies associated with the Lewisian Complex. A 2011 paper

Perspectives on Metamorphic Processes and Fluids. A. B. Thompson. Highlights the field of metamorphic petrology as one research area suitable for investigating the rocks of the LC.

A research paper in 2016 sums up a lot of the research work from 2010 onwards and considers tectonic models for the LGC.

Subduction or sagduction? Ambiguity in constraining the origin of ultramafic–mafic bodies in the Archean crust of NW Scotland, T.E. Johnson, M. Brown, K.M. Goodenough, C. Clark, P.D. Kinny, R.W. White. Precambrian Research (2016).